Qualified Workforce Mexico

A Historical Perspective on Workforce and Economic Development in Mexico

In the mid-20th century, Mexico embarked on a transformative journey known as Import Substitution Industrialization (ISI), a strategy aimed at reducing dependence on imports by fostering domestic industries. This period, particularly the 1950s and 1960s, witnessed substantial economic growth, earning it the moniker "the Miracle." However, this growth was characterized by a skewed income distribution, with capital accumulation playing a pivotal role.

Integral to Mexico's political landscape were organized labor groups, such as the Confederation of Mexican Workers (CTM) and the National Peasant Union (CNC). These groups formed the pillars of the ruling Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI), offering both control and electoral support. The political stability achieved during the PRI's dominance from 1946 to 2000 was often described as "the perfect dictatorship."

Despite the apparent success, challenges emerged in the late 1960s and 1970s, exposing the limitations of the PRI's institutional revolution. The presidency of Luis Echeverría (1970-76) marked a turning point. His policies, including income redistribution and increased government spending, led to economic deterioration, triggering a severe crisis in 1982.

The 1980s brought about economic reforms, including the Economic Solidarity Pact and the implementation of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) in 1993. While these measures opened up trade opportunities with the U.S. and Canada, they also sparked controversies, particularly regarding their impact on various sectors, including agriculture.

Despite these reforms, the post-crisis era spanning the 1990s and 2000s saw lackluster economic growth in Mexico. The trauma of past economic crises, particularly the "Lost Decade" of the 1980s, instilled a fear of growth. The central bank, Banco de México, adopted a singular focus on price stability, sidelining active promotion of economic growth.

A significant shift occurred in 2018 with the election of Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO). His victory marked a departure from traditional politics, bringing forth promises of increased spending on infrastructure, efforts to raise the real minimum wage, and a focus on revitalizing domestic agriculture.

As Mexico grapples with diverse challenges, including political transitions, global competition, security concerns, and public corruption, the success of AMLO's policies, labeled "Republican Austerity," becomes a closely watched economic experiment. The nation stands at a critical juncture, seeking to overcome the legacy of past crises and reignite economic growth under new leadership.

The Mexican Workforce

The Mexican workforce is characterized by its diversity, encompassing both production labor (direct labor) and highly skilled professionals (indirect labor). This diversity is well-suited for the manufacturing sector in Mexico, particularly considering the country's history of over 60 years in manufacturing, which has cultivated a well-trained and multigenerational pool of talent across various industries.

Direct Labor Categories

Unskilled Direct Labor

Unskilled direct labor in Mexico comprises employees with minimal education and training requirements. Typically holding no more than a high school diploma, these workers handle tasks that don't demand advanced skills. They are often not bilingual.

Semi-skilled Direct Labor

Semi-skilled workers in Mexico have a minimum of 2-3 years of experience in specific types of work. They may lack experience but possess natural skills, enabling them to be trained for higher-level tasks. Their pay is generally 20-30% higher than unskilled workers, contributing to lower turnover.

Skilled Direct Labor

Skilled direct labor is increasingly common, especially in industries such as aerospace, medical devices, and metal mechanics. Skilled workers have at least 5 years of specialized experience, earning double the salary of unskilled counterparts.

Indirect Labor Categories

Indirect labor includes facility management roles like plant managers, operations managers, production managers, and QC managers. The demand for engineers, including manufacturing, electrical, process, and mechanical engineers, is growing rapidly. Supervisors constitute the remaining segment of indirect labor.

The Mexican labor force draws from a young population, with 42% of its 117 million inhabitants aged between 20 and 49. This demographic diversity allows for a range of skills and expertise.

Evolution of Blue and White Collar Work

Historically, the white-collar and blue-collar dichotomy was based on the distinction between mental and physical tasks. White-collar work, associated with indoor and intellectual activities, required professional preparation. In contrast, blue-collar work involved manual tasks, often performed outdoors, and required minimal academic knowledge.

Over time, technological changes and automation have blurred the lines between these categories. While white-collar jobs have expanded significantly, there has been a qualitative shift in the nature of work. Jobs involving a combination of conceptualization and implementation have decreased, while those requiring only implementation have grown, even among traditionally white-collar occupations.

Research on the subjective well-being of white and blue-collar workers provides varied insights. Some studies suggest higher life satisfaction among white-collar workers, while others argue that white-collar workers may be more susceptible to the negative effects of job-related stress.

The Mexican labor force exhibits a diverse composition, encompassing a spectrum from unskilled to highly skilled workers. The historical categorization of white and blue-collar work has evolved, reflecting changes in technology and the nature of occupations over time.

Blue-Collar Workforce

- Dominant Sectors: Blue-collar workers in Mexico are often associated with industries such as manufacturing, construction, agriculture, and other manual labor-intensive fields.

- Employment Conditions: Blue-collar jobs may involve physical labor, often in manufacturing plants (maquiladoras), construction sites, or agricultural settings. Wages can vary based on the sector and skill level, with some workers facing challenges related to job security and workplace conditions.

- Labor Unions: Blue-collar workers in Mexico have a history of labor union participation, particularly in sectors like manufacturing. Labor unions play a role in negotiating wages, benefits, and working conditions for their members.

White-Collar Workforce

- Service Industries: The white-collar workforce in Mexico is prominently found in service industries such as finance, information technology, healthcare, education, and professional services.

- Education and Skills: White-collar jobs often require higher education and specialized skills. Professionals in this category include office workers, managers, educators, healthcare professionals, and IT specialists.

- Urban Concentration: White-collar jobs are more prevalent in urban areas, reflecting the concentration of industries and services in major cities.

- Corporate Culture: White-collar jobs are associated with corporate environments, where employees work in offices and may be involved in administrative, managerial, or knowledge-based roles.

Recent Trends and Challenges

- The Mexican workforce has been evolving with an increasing emphasis on technology and digital skills.

- Like many countries, Mexico faces challenges related to job automation and the need for workers to adapt to changing technological landscapes.

- In recent years, there has been a growing focus on improving education and skills training to meet the demands of a changing job market.

Skills and advantages

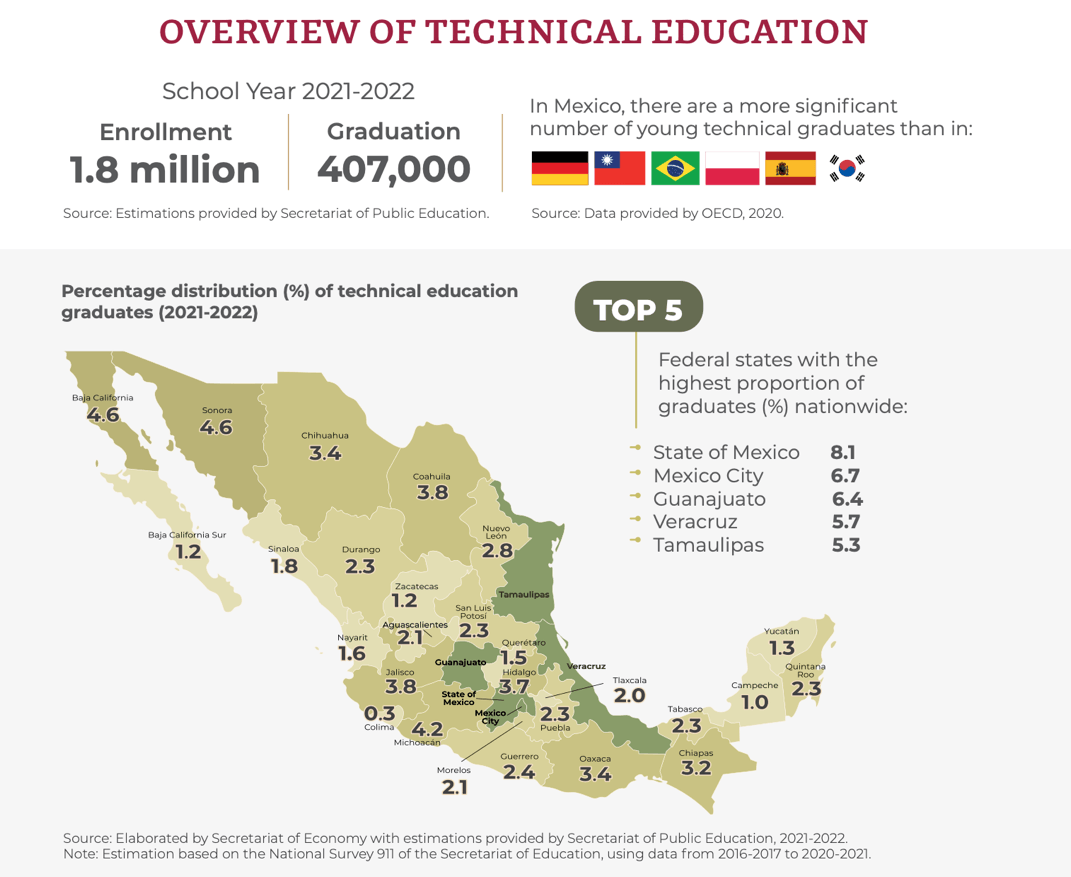

Mexico's technical education system stands out as a robust competitive advantage for nearshoring, representing one of the largest and most specialized systems globally at the secondary education level. Linked closely to the private sector, this system focuses on crucial industries vital for economic growth, making it an ideal training ground for the skilled workforce demanded by modern manufacturing.

The technical education talent pool in Mexico is impressive, surpassing that of many countries, including Brazil. The higher secondary education system encompasses three models: general or propaedeutic, technological, and professional-technical, each serving specific educational needs. Within the technological and technical secondary level, students aged 15 to 17 pursue technical careers tailored to various fields, such as industrial, service, commerce, agriculture, fishing, and forestry.

The Secretariat of Public Education (SEP) reports a significant increase in technical graduates, reaching an estimated 407 thousand in the 2021-2022 period. This surge is particularly notable in fields like Programming, Computer Support, and Systems Maintenance Careers, constituting 21% of the total technical graduates. Additionally, 8% graduate in areas related to Electromechanics, Automotive Industry, Motors, and Industrial Maintenance, showcasing the diversity and specialization of the technical education offerings.

Mexico's commitment to technical education is underscored by its position among the top five OECD economies allocating the largest public budget to the secondary education level. In 2020, Mexico led in terms of enrolled students in technical education within OECD countries, with a substantial margin of 1.7 million students, indicating the scale and popularity of technical education in the country.

Furthermore, in the same year, Mexico ranked first in the number of technical education graduates within the OECD, with 400 thousand individuals completing their technical education. This achievement positions Mexico as a frontrunner in producing a skilled workforce ready to contribute to the demands of evolving industries.

The data presented by the Secretariat of Economics, with information from OECD, highlights Mexico's strategic focus on technical education as a key driver for economic growth and nearshoring. The sizable talent pool, diverse specializations, and significant public investment underscore the country's commitment to nurturing a skilled workforce that aligns with the needs of contemporary industries. This technical education advantage solidifies Mexico's position as an attractive destination for companies seeking to invest in or relocate their production operations.

Mexico boasts a young and industrious workforce, a key factor that positions it as an attractive destination for nearshoring. With an average age of 29, Mexico's population is youthful, and approximately 42% of its 117 million inhabitants fall within the 20 to 49-year-old age bracket. This demographic composition ensures a continuous influx of labor into the market, mitigating concerns related to an aging workforce.

Moreover, the Mexican government has made substantial investments in education to harness its demographic dividend effectively. The average schooling for Mexicans increased from 7.5 to 9.7 years between 2000 and 2020, signaling a commitment to enhancing the skill set of the labor force. Scholarships provided to over 10 million students in 2022, amounting to an investment exceeding $2.2 billion, exemplify a proactive approach to support education.

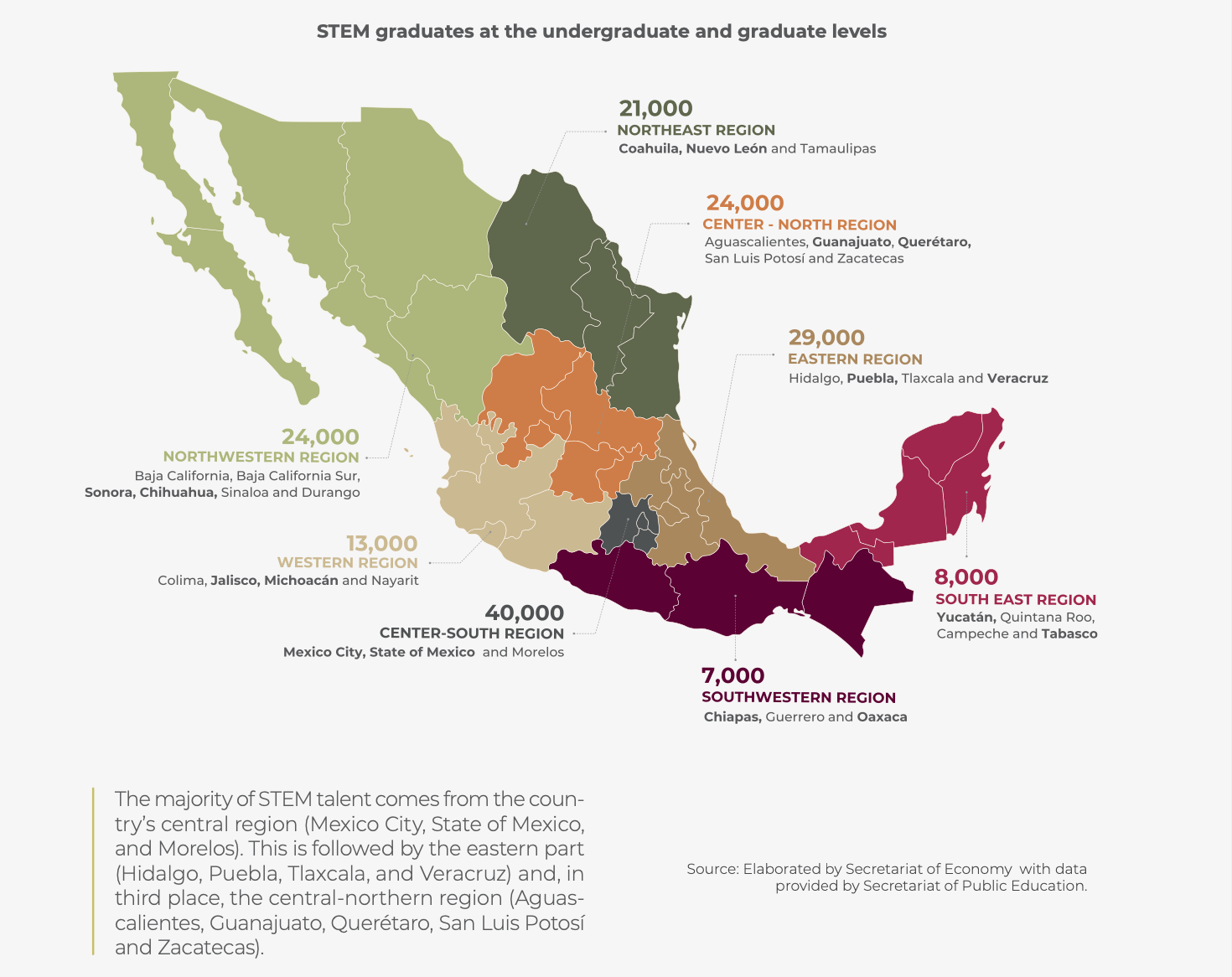

In higher education, Mexico allocates around $9.1 billion, supporting 1,335 undergraduate programs in fields such as information technology, engineering, manufacturing, and construction. The focus on STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics) disciplines is evident, with 37.5% of graduates specializing in these areas. Mexico ranks as the second country with the most engineers among OECD nations, showcasing its dedication to producing skilled professionals.

The commitment to technical education is a standout advantage for nearshoring. Mexico's technical and technological system at the secondary education level is among the largest globally, offering three models: general, technological, and professional-technical. With a talent pool twice the size of Brazil, Mexico's secondary education system emphasizes crucial industries like industrial, service, commerce, agriculture, fishing, and forestry fields.

The collaborative efforts between the education system and industries ensure that curricula remain relevant to technological advancements, preparing the workforce for the evolving needs of global supply chains. This alignment with industry requirements and the emphasis on STEM education make Mexico a competitive force in attracting foreign investment and establishing itself as a hub for nearshoring. The Mexican workforce, particularly young technicians, and specialists, serves as a cornerstone for elevating productivity and enhancing competitiveness across industries.

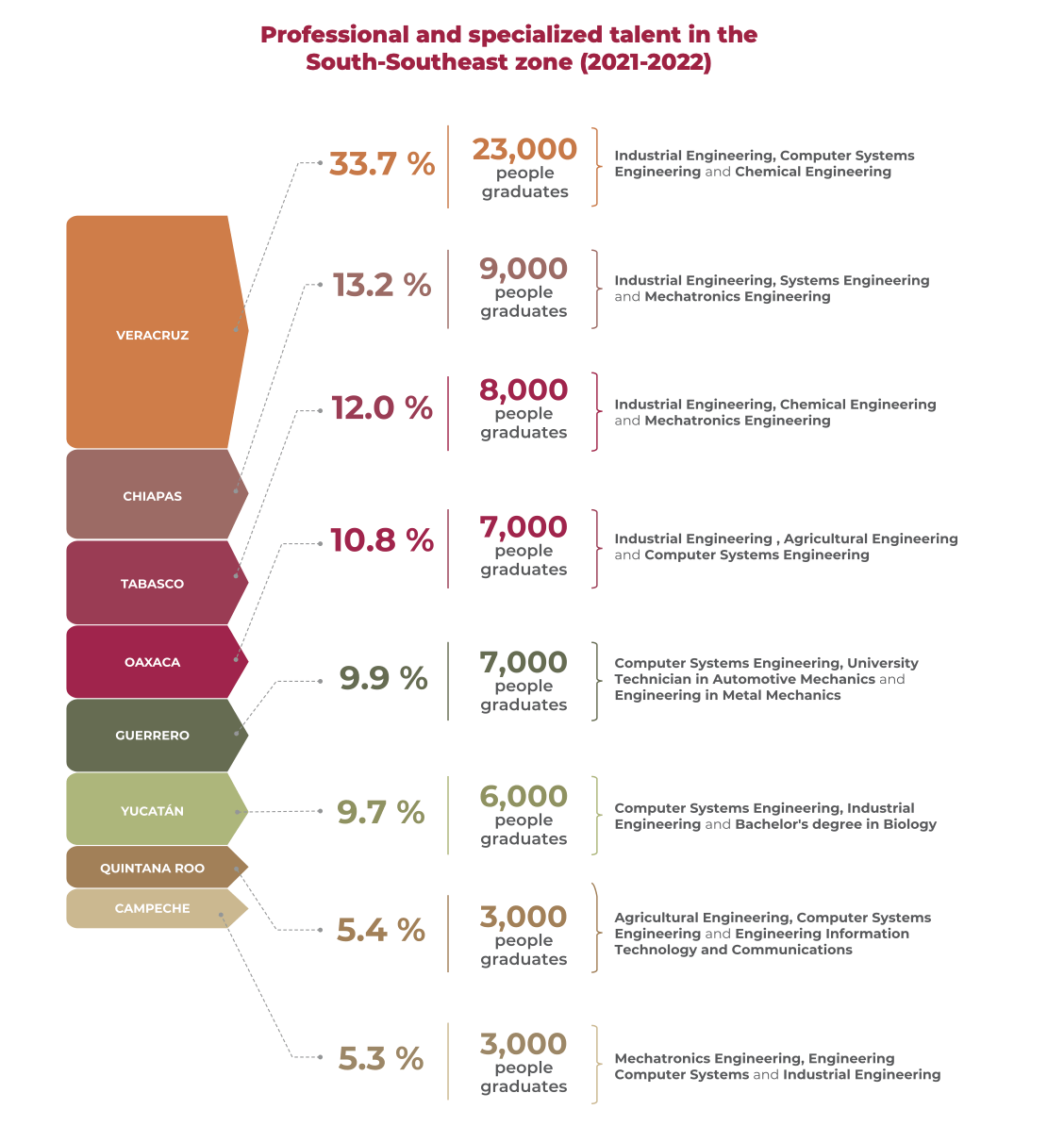

Talent for specific industries

Electrical and electronic industries

Mexico's electrical and electronic industries have thrived with the presence of global giants like Intel, Flextronics, Lenovo, Samsung, and Foxconn, solidifying its position as the fifth-largest supplier of household appliances globally.

Key Graduates for Electrical and Electronic Industries (2021-2022):

- Electricity and Industrial Electricity: 8,000 graduates, concentrated in Veracruz, Sonora, and Mexico City.

- Mechatronics: 10,000 graduates, particularly in Guanajuato, Coahuila, and Baja California.

- Electronic Systems Maintenance: 2,000 graduates, mainly in Mexico City, Coahuila, and Nuevo Leon.

Graduates Include Careers Such As:

- Computer Systems Engineering

- Information Technology Engineering

- Electronics Engineering

- Computer Engineering

Noteworthy Graduates:

- Bachelor: 28,356 graduates, concentrated in the State of Mexico, Nuevo Leon, Guanajuato, and others.

- Higher Technical University (TSU): 4,709 graduates, primarily in Veracruz, State of Mexico, Mexico City, and more.

- Master’s Degree: 1,677 graduates, predominantly in Guerrero, Puebla, Veracruz, and others.

Mexico holds a unique opportunity to integrate into the global semiconductor value chain, given its proximity to the United States, a high supply of STEM talent, and robust infrastructure supported by institutions like CIMAV, CIDESI, and INAOE. These factors position Mexico as a key player in the global semiconductor industry.

Automotive industry

Mexico's automotive sector, ranking seventh globally in vehicle production, plays a pivotal role in the nation's economic sustainability. A notable exporter of auto parts and a primary supplier to the U.S., the industry showcases Mexico's manufacturing prowess.

Key Industry Features

- Global Presence: Leading companies like Ford and BMW have strategically chosen Mexico for critical operations, emphasizing product development and advanced technologies.

Adapting to Electromobility

- In response to the global shift toward electromobility, Mexico's educational institutions, including Conalep, have revamped technical curricula. Graduates are well-versed in converting internal combustion engines to electric power.

Skillful Workforce

- Mexico's automotive industry boasts around 13,000 skilled graduates annually. These professionals meet industry demands, ensuring a continuous stream of talent in alignment with evolving automotive technologies.

Industry-Education Collaborations

- Collaborative initiatives between educational institutions and industry giants, such as General Motors, John Deere, MG Motor, and UNAM, ensure graduates are well-prepared for the sector's demands. These collaborations focus on specialized areas like Autotronics, Industrial Maintenance, and High Voltage Expertise.

Working hours and salaries

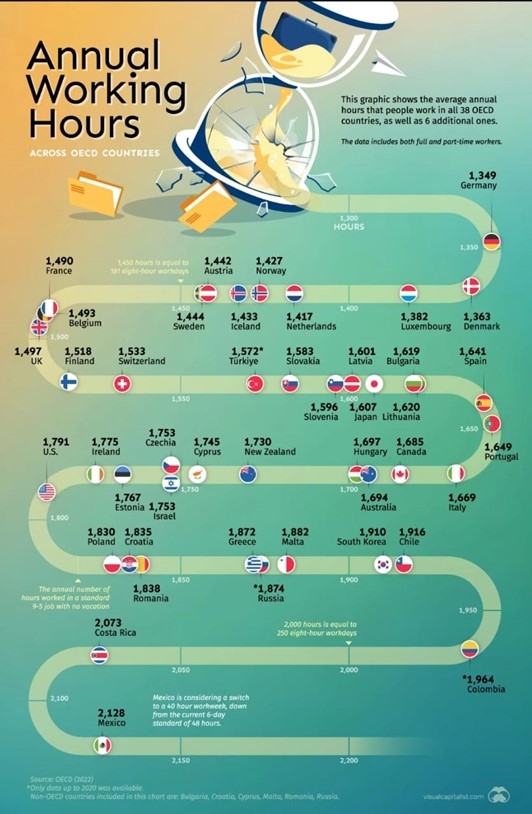

In Mexico, the labor force is a key attraction for businesses aiming to enhance competitiveness and flexibility. Understanding the standard work week, including shifts, maximum working hours, breaks, and overtime calculations according to Federal Labor Law is crucial for companies.

As per Article 61 of the law, there are three work shifts, each with distinct maximum hours:

1. Day Shift: Between 6:00 AM to 8:00 PM (maximum of 8 hours per shift).

2. Night Shift: Between 8:00 PM and 6:00 AM (maximum of 7 hours per shift).

3. Mixed Shift: Combines day and night hours, with no more than 3.5 during the night (maximum of 7.5 hours per shift). If exceeding 3.5 night hours, it's considered a night shift.

Overtime applies when shifts exceed the maximum hours. Employees can work up to three extra hours per shift, three times a week (nine hours), paid at double the hourly salary. Beyond nine hours in a week, payment is at triple the hourly wage.

Employers and employees can agree on daily and weekly working hours, provided they don't surpass legal limits. Employers must allow one day of rest per week and a minimum 30-minute break per shift, although many offer additional break time.

While full-time employees usually work a 6-day, 48-hour week (Monday to Saturday), flexibility exists for 4 or 5 workdays with the same weekly maximum hours.

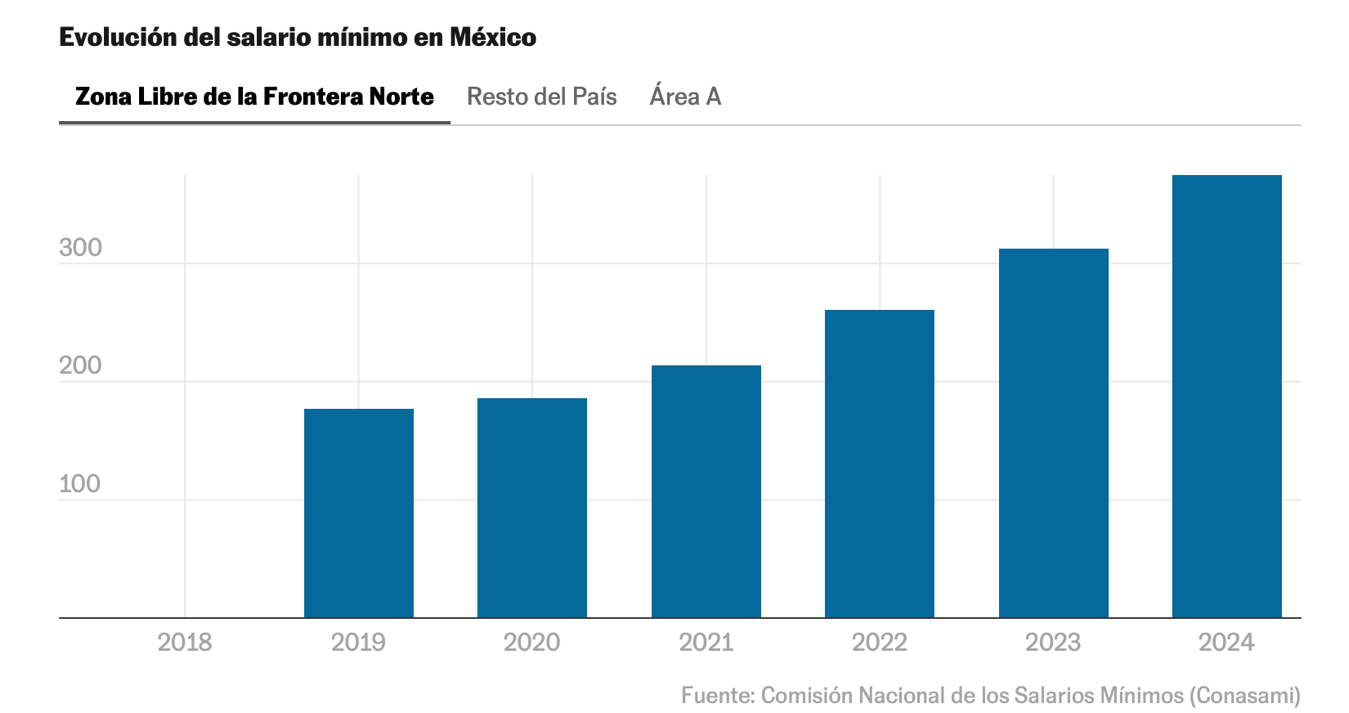

Increasement of salaries in Mexico

As of January 1, 2024, the minimum wage in Mexico will be increased to 249 pesos per day, reflecting a 20% boost. This decision was reached unanimously by the Consejo de Representantes de la Comisión Nacional de Salarios Mínimos (Conasami), comprising representatives from businesses, labor unions, and the federal government.

President Andrés Manuel López Obrador highlighted this achievement during a press conference, emphasizing the historical significance of the increase. The minimum wage has substantially risen during his tenure, starting from 88 pesos per day in 2018 to the upcoming 249 pesos per day in 2024.

Notably, in the northern border free zone, the daily minimum wage will surge from 88 pesos in 2018 to 375 pesos in 2024. This considerable increase, which the president deems historic, addresses economic dynamics that hadn't been witnessed for at least 50 years.

While the 20% wage increase is below the 25% demand from unions, it surpasses the 12.8% proposed by the Confederación Patronal de la República Mexicana (Coparmex).

These wage adjustments are occurring amid a broader context of inflation deceleration in Mexico in 2023. Despite a slowing trend, the recent increase aligns with efforts to enhance workers' financial well-being. The president, recognizing the importance of consensus in previous wage negotiations, plans to invite representatives from labor and business sectors to discuss this wage hike further.

Alday, R. (2020). Labor in Mexico.Retrieved from https://doingbusiness-mexico.com/labor-in-mexico/

Bloomberg. (2023). Salario mínimo en México aumenta 20% para 2024: ¿Cuántos pesos subió?Retrieved from https://www.elfinanciero.com.mx/economia/2023/12/01/salario-minimo-en-mexico-aumenta-a-248-pesos-con-93-centavos-para-2024/#

Garibay, M. (2022). What are the Standard Work Hours and Work Week in Mexico?. Retrieved from https://www.americanindustriesgroup.com/blog/what-is-the-standard-work-week-in-mexico/

NAPS. (2023). Labor in Mexico.Retrieved from https://napsintl.com/manufacturing-in-mexico/labor-in-mexico/

Salvucci, R. (2023). The Economic History of Mexico. Retrieved from Economic History Association: https://eh.net/encyclopedia/the-economic-history-of-mexico/

Secretariat of Economy. (2023). Mexican Talent for economic growth and nearshoring. Retrieved from https://www.gob.mx/cms/uploads/attachment/file/828153/talento-mexicano_ing.pdf

Temkin, B., & Ibarra, J. C. (2018). Las dimensiones de la actividad laboral y la satisfacción con el trabajo y con la vida: el caso de México.Retrieved from Scielo: https://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?pid=S2448-64422018000300507&script=sci_arttext_plus&tlng=es